Venture Math: How VCs Value Startups

In my course on digital health investing at Columbia Business School, real founders pitch their businesses, and my students — with their VC hats on — write investment memos. The goal of the class is to get students to start thinking like VCs. Even if they have no intention of going into VC, my hope is to help them build the evaluation skills helpful in many professional settings.

Because the course is short, their memos are a binary “yes” or “no,” with arguments to back up why they would invest, or not. I often get requests from students who want to take it further and understand startup valuations. And so this year, I worked with one of my students, Jack Vailas, on an independent study to create a guide that breaks down the art and science behind venture capital deals.

In this post, we'll cover key terms like pre-money and post-money valuation and explain how dilution works in practice. We then outline six common methods VCs use to value startups, from the Dilution Method to the "VC Method." Finally, we’ll explain valuation vs. price and how market conditions affect dealmaking.

Whether you're preparing for your first pitch or just want to understand VC math better, we hope this guide is helpful.

In this post we make several simplifying assumptions to avoid over-complication. We also reference hypothetical entities “ABC Ventures” and “TargetCo”, these do not represent real entities.

Key terms and concepts

To start, let’s define key terms with an example. Suppose ABC Ventures invests $5M into TargetCo at a $10M valuation (more on how they might have come up with that valuation later). The pre-money valuation is the company's valuation before funding, so $10M and the post-money valuation is the valuation after funding, so $15 ($10M pre-money plus the $5M investment).

Continuing with the example, suppose the founders owned 100% of TargetCo before the $5M investment. Assuming they did not participate in the financing, they now own 66.7%. In other words, their ownership stake has been diluted. However, the dollar value of their ownership is still $10M since they now own 66.7% of a $15M company.

In our example, ABC Ventures valued TargetCo at $10M. This is called a priced round, where a company’s valuation is made explicit, allowing VCs to purchase shares at a specified price. The alternative is a non-priced round, which is common during the idea and seed stage, where investors essentially say, it’s too early to put a valuation on this company, so let’s not worry about that now.

In these cases, VCs use instruments such as convertible notes or simple agreements for future equity (SAFE). While there are differences, they both function by enabling VCs to invest money today in exchange for future company shares during a subsequent priced round where they can explicitly value their investment.

The main difference between convertible notes and SAFEs is that convertible notes are debt instruments (SAFEs are not) and thus come with a maturity date and accrue interest. Convertible notes are like most other loans, except instead of getting paid back principal plus interest, you get repaid with equity.

What convertible notes and SAFEs do have in common are valuation caps and valuation discounts. Using SAFEs as an example, a valuation cap sets the maximum price at which the SAFE will convert to equity, guaranteeing a maximum future price no matter how the next investors value the company. A valuation discount is a promissory reduction to the established share price during the next priced round. If both clauses are present, once the SAFE converts, the VC will receive the better of the two outcomes.

Let’s use an example. Suppose ABC Ventures invests $1M in TargetCo’s Seed round via a SAFE with a $5M cap and 20% discount. At this point, they really only have the promise to purchase shares in the future. During the next priced round, a new investor values TargetCo at $10M with a share price of $1.00. To calculate ABC Ventures’ implied share price using the cap, divide the $5M cap by the $10M valuation (i.e., $0.50 per share). To calculate ABC Ventures’ implied share price using the discount, multiply the $1.00 share price from the priced round by 1-20% (i.e., $0.80). Since the cap yields a lower share price, ABC Ventures will use this and obtain 2M shares in return for their $1M investment.

Valuation

Depending on the stage of the company, VCs will use a number of methods to value a company. For early-stage companies, there is barely any data, so VCs generally focus primarily on the team. They want to know that this is the right team for this company, known as Founder-Market Fit. For later-stage companies, VCs focus primarily on execution. They want to see traction trending in the right direction, known as Product-Market Fit. At this stage, there is more data, prompting the use of more elaborate valuation methods.

VCs will typically have a valuation range in mind for companies at various stages, which fluctuates with market conditions. The goal is to have a high-level sense of the current financing environment before entering company-specific data. For example, a VC evaluating a US-based digital health company raising its Series A may quickly pull together some derivation of the following analysis to set valuation expectations.

In conjunction with comparable valuation benchmarks, there are a handful of valuation methods used. It is also common for VCs to use several methods to triangulate a reasonable valuation. When deciding which method to use, it really depends on available information. If you are evaluating a later-stage deal with a lot of available information, it may be worth using a more involved method. If you are evaluating an early-stage deal with nothing more than a founding team and a business plan sketched on a napkin, a less involved method is more appropriate. And, to reiterate, the math is not complicated. In fact, these methods are more akin to simple frameworks. Below are six common valuation methods used in VC:

Dilution Method

The Dilution Method calculates the pre-money using investment and dilution. Have you ever watched Shark Tank when they say, “I will give you X million for Y percent of your company”? This is the dilution method at work. VCs often have ownership targets, and this method helps them meet this percentage of ownership.

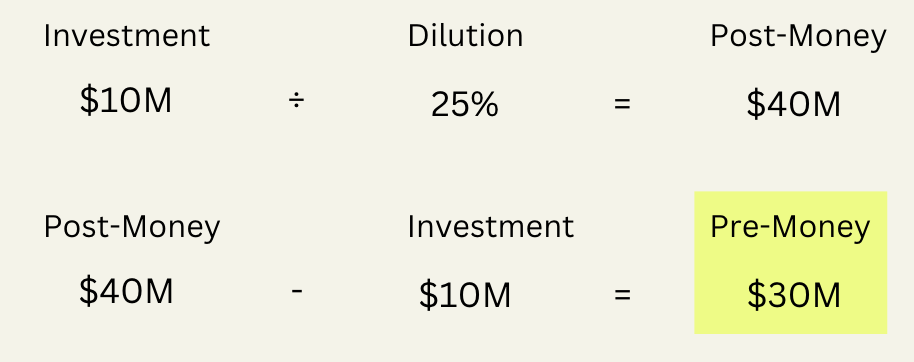

It helps to remember the following: investment ÷ dilution = post-money and post-money – investment = pre-money.

Thus, if you know the investment and dilution, you can calculate the pre-money. Let’s assume you invest $10M to own 25% of a company; the implied pre-money is $30M.

Step-Up Method

The Step-Up Method calculates the current pre-money by multiplying the previous post-money by a multiple. When the multiple is >1x, it’s an up round (aka a step-up). When the multiple is <1x, it’s a down round (aka a step-down). When the multiple equals 1x, it’s a flat round.

In Q2 2024, 74% of deals were up rounds, and 22% of deals were down rounds. Ultimately, the multiple depends on investor appetite and how the company performed vs. expectations. Assuming a 2x step-up, a company with a previous post-money of $50M would be valued at $100M.

The Milestone Method

The Milestone Method calculates the pre-money by leveraging comparable company valuations at comparable milestones. Many industries have distinct developmental milestones (e.g., medical devices and therapeutics). If comparable companies raised around X after completing milestone Y, it is reasonable to assume that a company that just completed milestone Y could raise around X. Let’s assume comparable companies raised around $30M after completing milestone A. If we value a company that also completed milestone A, the pre-money should be roughly the same, $30M.

Scorecard Method

The Scorecard Method calculates the pre-money by multiplying the average value of comparable companies by an adjusted multiple. This approach builds on the milestone method while allowing for adjustments based on how a company compares to its peers. The scorecard method has four steps:

Average the pre-money valuations of similar companies at similar stages

Determine a set of key criteria and assign weights based on importance

Score each criteria as a 0, 1, or 2 for the company in question (0: worse than peers, 1: same as peers, 2: better than peers)

Calculate the weighted average score and multiply that by the average pre-money from step 1

The “VC Method”

The “VC Method” calculates the pre-money by computing an exit value and discounting it back to the present. The VC method is one of the more common valuation methods. To use this method:

Determine your fund’s desired IRR and investment amount

Assume an exit year and forecast the valuation metric until exit (e.g., revenue)

Calculate an average valuation multiple from comparable companies (e.g., enterprise value (EV)/revenue)

Multiply the metric by the multiple to derive an exit value

Discount the exit value back to the present using your fund’s desired IRR.

This yields the current post-money. Thus, subtract the investment amount to calculate the pre-money.

Scenario Analysis

Scenario Analysis calculates expected returns based on several scenarios. This method was popularized by Bessemer Venture Partners, as seen in their investment memos. To run a scenario analysis:

Ideate possible exit values, years, and probabilities

Calculate expected proceeds and exit year

Calculate the implied multiple on invested capital (MOIC) and internal rate of return (IRR)

The following example assumes you invest $10M to own 25% of a company:

Pricing

We just discussed several common valuation methods used in VC, but what about pricing? Valuation is the art and science of determining what something is worth, whereas price is what you pay. To understand price, we must acknowledge buyer and seller incentives. In VC, like all investing, investors want to “buy low and sell high” to maximize expected returns, whereas existing shareholders want to raise capital and minimize dilution.

For example, suppose ABC Ventures is considering a $5M investment in TargetCo, which it thinks will exit at $100M in 5 years without any additional dilutive financing. Let’s also assume, using the methods outlined above, ABC Ventures and existing shareholders believe TargetCo is worth $30M (aka fair market value).

ABC Ventures is incentivized to price the deal below fair value to maximize expected returns:

If the deal is priced at $20M, ABC Ventures gets 5.0x MOIC or 38% IRR

If the deal is priced at $40M, ABC Ventures gets 2.5x MOIC or 20.1% IRR

Existing shareholders (including the founders) are incentivized to price the deal above fair value to minimize dilution:

If the deal is priced at $20M, shareholders are diluted by 25%

If the deal is priced at $40M, shareholders are diluted by 12.5%

If ABC Ventures and existing shareholders cannot agree on a price, there are several additional levers each can pull to bridge the gap. These “levers” come from different rights and provisions found in term sheets.

There are also several external factors that affect price, such as market sentiment, the number of term sheets, and the interest rate environment.

Understanding how interest rates impact prices allows us to make sense of what happened to many companies over the past few years. When rates are low, demand for VC as an asset class increases, meaning limited partners like pension funds are more likely to invest in VC versus bonds or other assets. When the supply of capital increases without a corresponding increase in the number of investable opportunities, prices also tend to increase. This is what happened during the pandemic: The low interest rate environment drove deal prices up, especially in healthcare.

You may be wondering, “What’s the big deal with inflated deal prices?” To answer this, we need to look at the big picture. In general, startups raise capital every 1.5 years. And ideally, prices reflect fair market value and increase steadily over time. This allows new and existing investors to realize attractive returns, both long-term and “on paper” between financings. The following example outlines such a scenario.

But what if low interest rates in year 1.5 cause investors to bid up the price? At first, this is great for existing shareholders who, on paper, realize a 69.0% return. However, assuming exit timing and value in year 4.5 hasn’t changed, this is not great for new investors who now only expect a 14.0% return.

When it comes time to raise in year 3, new investors will price the round to realize an attractive expected return at exit. However, in our example, existing shareholders aren’t happy since, on paper, their return from year 1.5 to year 3 is 0.0%. This creates a difficult deal environment in year 3 where existing shareholders may wait for more attractive bids; however, the longer they wait, the more cash they burn. And, the shorter the runway, the less leverage they have during subsequent negotiations.

Summing it up

If you take anything from this crash course, remember:

You can use multiple valuation methods to triangulate a reasonable fair market value.

Valuation (what something is worth) and price (what you pay) are distinct concepts influenced by various factors, including market conditions, negotiating leverage, and interest rates.

Take a long-term view when pricing deals— artificially inflated valuations might feel good in the moment but can create significant challenges in future funding rounds. Remember the big picture.

For additional resources on venture math, check out this deck and problem set. We hope this helps!