Why Are Americans So Unhealthy?

Yesterday’s article, How Healthcare Works in the Five Healthiest Countries, generated a ton of great comments and questions on LinkedIn and Twitter. thought it was worth sharing some of the thoughts, and answering some of the questions that came up.

Dave Cluley commented:

Keeping people sick keeps the medical industry in business. Medicine is a service industry that produces nothing. While it makes people 'better,' it doesn't return them to their condition prior to being sick. Seems like we are all paying a lot of money for not much.

Dave is right. It’s certainly frustrating to navigate a system with perverse incentives. Often, these misaligned incentives encourage behavior that prioritizes profit over patient well-being, leading to short-term gains at the expense of long-term health outcomes. They can cause inefficiencies, overutilization of services, and a focus on treating illness rather than preventing it. These incentives can stifle innovation and discourage meaningful collaboration amongst stakeholders. Ultimately, the challenge lies in re-imagining and restructuring our healthcare system to ensure that all players are aligned towards the shared goal of enhancing human health and wellbeing.

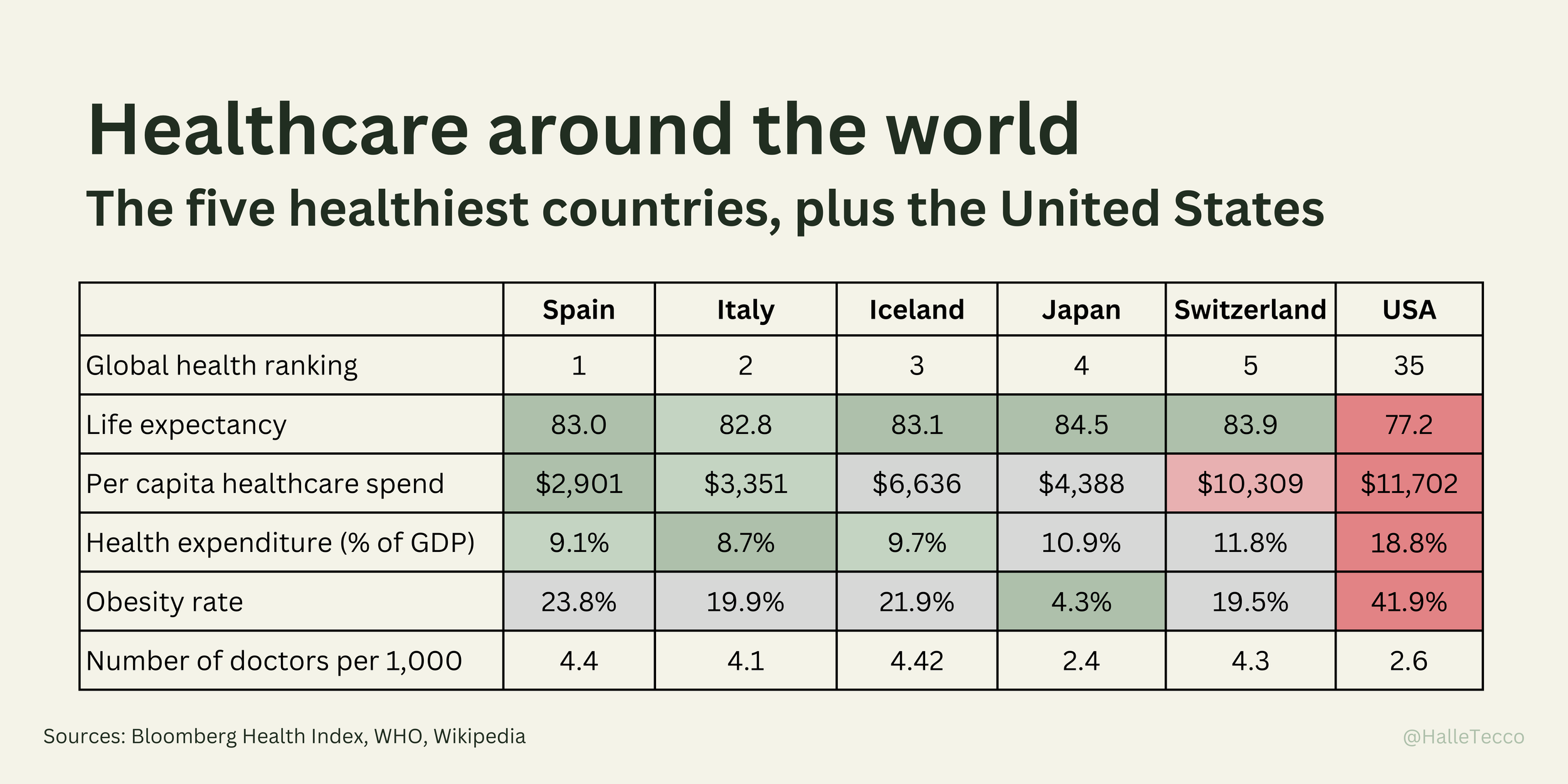

So let’s dive in on the discussion. First, lots of folks pointed out the obesity rate in the U.S. being 42%, which is a whopping 134% higher than the average of the other five nations, as a reason for our high cost of care.

Eddie Ovey asked:

Out of curiosity, has there been any research on the cost of care for Americans that are obese vs. those that aren't?

Yes. One study found that Americans with obesity have higher annual medical care costs by $2,505 or 100%, with costs increasing significantly with class of obesity, from 68.4% for class 1 to 233.6% for class 3.

The CDC estimates that obesity alone costs the US healthcare system a colossal $147 billion annually. To put that into perspective, if we could effectively address and lower obesity rates to remove this cost, we would see around a 4% reduction in our overall healthcare expenditures — a decent step towards controlling the spiraling costs of healthcare.

So many people commented on the food

Kat Rozanna commented:

As a European who has had the opportunity to experience living in both the United States and Europe, I have had the chance to make comparisons between the food cultures. In my personal observation, American cuisine tends to be heavily processed, which may contribute to concerns regarding its overall healthiness. Another aspect of is the prevalence of large portion sizes and the tendency to consume meals while driving, in a hurry, or in stressful situations. Unfortunately, these habits do not promote a healthy approach to eating, which is disheartening to witness.

Mateusz Tylicki commented:

Life expectancy and obesity are influenced significantly by factors outside of traditional healthcare e.g food quality, sugar / UPF consumption, exercise / movement, stress exposure etc. Countries like Spain and Italy nail it on those fronts and the US learn from them.

Kunaal Patel commented:

I wonder if there’s a food quality index score for every country. From personal experience it seems like the food quality in the US (even organic foods) seems to significantly lower than europe. I’ve been able to eat foods abroad (dairy, pastry) that I have issues w in the US

Let’s look at some stats I found on nutrition:

On average, we do consume slightly more (3.5%) calories than our peer countries, 60% more meat (which isn’t necessarily a bad thing), and 10% more sugar.

Plus, the food we do eat tends to be more processed. In fact, the U.S. (and the U.K.) have the highest rates of energy intake from ultra-processed food (UPF) in the world, while Mediterranean countries such as Italy showing the lowest level.

When it comes to food security, food in the U.S. is 2.55% less affordable than these peer countries, and 10.14% less accessible. However, in terms of food quality and safety, our food scores 15.32% higher.

The American diet is often characterized by larger portion sizes (supersize me!) and higher consumption of processed foods, fast foods, sugar-sweetened beverages, and high-calorie snacks. These foods are typically energy-dense but nutrient-poor, leading to weight gain. In contrast, the diets in the other countries, such as the Mediterranean diet in Spain and Italy or the balanced diet in Japan, are typically rich in whole foods, lean proteins, fish, fruits, and vegetables.

Listen to this Heart of Healthcare Podcast episode with Michael Moss, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author of #1 New York Times bestseller book Salt Sugar Fat and Hooked: Food, Free Will, and How the Food Giants Exploit Our Addictions.

And the fact that we’re not as active as we should be (or are we?)

Physical inactivity is a significant issue in the U.S., where many people have sedentary jobs and exercise infrequently. In Japan and most of Europe, walking or biking as part of daily commute is more common, and this regular physical activity helps maintain a healthy weight.

However, a study in the Lancet found that self-reported physical activity in the U.S. isn’t an outlier compared to these other countries. Here’s the percent in each country that reported doing at least 150 min of moderate-intensity, or 75 min of vigorous-intensity physical activity per week, or any equivalent combination of the two:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30357-7

Keep in mind, this is self-reported data. Someone in Italy, for instance, who is less likely to own a car, may not even consider their daily walk to the store or work as exercise.

Speaking of cars, we can’t overlook our dependency on cars in the U.S. - with 919 cars per 1,000 people, 35% more than our peer countries. This poses significant public health and environmental challenges, contributing to lower physical activity levels, obesity, and respiratory problems.

Car ownership

Trixi Pudong pointed out:

In contrast to the countries on that list, only the US is so car-oriented. Americans do. not. walk. Having lived in Asia and EU, I feel the US oil-industry dominance is the same capitalist abuse as in the US food and healthcare.

What about stress?

Some folks mentioned stress, work, and lack of sleep as potential contributors to poor health in the U.S., so let’s take a look.

Are we more stressed? Absolutely yes. The Gallup Global Emotions Report asked people, ‘Did you experience stress during a lot of the day yesterday?’ U.S. respondents reported 46% higher stress than the other five countries:

Stress levels

This higher levels of stress reported by Americans certainly has an impact on overall health and well-being. And think about the vicious cycle: unaffordable healthcare leads to stress, and stress leads to poorer health.

Not to mention elevated stress due to economic inequality, with the U.S. reporting a Gini coefficient 40% higher than its peer countries. This inequality can lead to social tension, financial insecurity, and increased work hours (14% more annually in the U.S.) to maintain a decent living standard, all of which contribute to higher stress levels.

Source: OECD (2022)

Ida Sefer asked:

Did you get a chance to analyze sleep & rest time? Constant stress due to lack of sleep contributes to insulin resistance. All of the countries you mentioned have a standard of taking time off and resting. That’s not really a standard in the US where there is an expectation to work even when you are sleep deprived or ill.

Poor sleep can further compound health issues, leading to conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, and depression. But looking at the data, we get about the same amount of sleep as these other countries (7 hours and 10 minutes per night). Still, the CDC has warned that more than 1 in 3 Americans are sleep-deprived.

Sleep

Do we need more doctors?

Several folks were shocked to learn that we have fewer doctors per capita than the other countries (except Japan).

Doctors per capita

Today there are over 1M active physicians in the U.S., an increase of more than 17% over the last decade. This number is growing mostly because of an increase in specialists. The number (and percent) of primary care physicians (PCPs) has actually fallen in this time.

Yet we have fewer doctors per capita compared to these other countries (except Japan). And many believe we are facing a looming physician shortage, with estimates from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), suggesting a shortfall of between 37,800 and 124,000 physicians by 2034.

What’s driving the shortage? The time and cost of medical training, increasing physician burnout, rising malpractice suits, and growing disenchantment with the complexities and inefficiencies of the healthcare system.

Medical education in the U.S. is a lengthy and expensive process. Typically, it takes at least 11 years after high school (4 years of undergraduate study, 4 years of medical school, and 3 to 7 years of residency) to become a doctor. To contrast, most European countries have one continuous six-year program. The high cost of this education often results in significant student loan debt, potentially deterring many from pursuing a career in medicine.

Source: OECD Health Statistics, 2019

Nearly a third of Americans lack access to primary care services, and 40% of U.S. adults say they’re delaying or skipping care due to the financial costs.

So it’s not surprising to see, according to OECD data, that Americans have fewer doctor consultations annually than these other countries. Looking at Japan, which has the lowest rate of doctors per capita, also have the highest rate of consultations per year. I’m wondering how that works.

So what can we do?

I agree with Mike Townsend who says:

Decoupling employers from health insurance would be the most effective short term goal.

And Dr. Sima Pendharkar who commented:

I think placing more emphasis on prevention , health education in schools at an early age would be impactful . I always think of a 50 year pt came into hospital with heart attack his primary care doc had left town one year prior

Sami Inkinen (who I had on my podcast — great episode) brings up:

It's insane that kids don't get free wholesome meals at schools or can drink government subsidized soda, just so we can pay for $10k weight loss treatments for teenagers. This is how we end up 50%+ of pop obese and dealing with $100k+ heart surgeries by early middle age. Or how we don't support new parents, etc.

Dino William Ramzi suggested:

Improve primary care infrastructure.

Less practical, Tom S. suggested:

Ban fast food and make vegetables free

There is certainly not one factor that lead us to our current health status. Diet, exercise habits, stress levels, socioeconomic disparity, and systemic healthcare challenges have all contributed to rising obesity, rising chronic disease burden, lower life expectency. and ultimately the high cost of healthcare.

And just as multiple factors got us into this mess, it will take a multifaceted approach and collective action to get us out. There is no magic bullet, no one-size-fits-all solution. Instead, we must undertake a comprehensive, concerted effort to address each contributing factor, from promoting healthier dietary choices and active living, to reducing income inequality and stress levels, to reforming our healthcare system. By doing so, we can hope to foster a healthier society that thrives not only in economic prosperity (think of all the money we can save!), but also in physical wellbeing and quality of life.